“中國歷代人物傳記資料庫”的版本间的差异

Tsui lincoln(讨论 | 贡献) (→外部链接) |

Tsui lincoln(讨论 | 贡献) (→History) |

||

| 第7行: | 第7行: | ||

CBDB 始於社會史專家郝若貝(1932-1996)的工作。<ref>{{cite article|last1=Smith|first1=Paul J.|title="Obituary: Robert M. Hartwell (1932-1996)"|date=1997|publisher=Journal of Song Yuan Studies 27}}</ref>郝若貝首次使用關係型數據庫研究宋代官員的社會和家庭網絡。意識到學界缺乏用於研究中國中古社會史的大型數據集之後,他便踏出了搜集數據的第一步,並通過數據分析,試圖對中國歷史的變遷提出一些有意義的回答。郝若貝透過人名、地名、官僚系統、親屬關係和社會關係等欄目來為數據建立結構。 | CBDB 始於社會史專家郝若貝(1932-1996)的工作。<ref>{{cite article|last1=Smith|first1=Paul J.|title="Obituary: Robert M. Hartwell (1932-1996)"|date=1997|publisher=Journal of Song Yuan Studies 27}}</ref>郝若貝首次使用關係型數據庫研究宋代官員的社會和家庭網絡。意識到學界缺乏用於研究中國中古社會史的大型數據集之後,他便踏出了搜集數據的第一步,並通過數據分析,試圖對中國歷史的變遷提出一些有意義的回答。郝若貝透過人名、地名、官僚系統、親屬關係和社會關係等欄目來為數據建立結構。 | ||

郝若貝教授去世後,將數據和相關程序遺贈予哈佛燕京學社。當時此數據包含超過25,000個歷史人物,4,500 條書目信息,以及他在歷史地理信息系統方面積累的成果。哈佛燕京學社隨後對此數據失去了興趣,所以自 2005 年開始,哈佛大學的包弼德教授開始著手公開發佈郝若貝的成果,並進行擴展。來自加利福尼亞大學爾灣分校的中國文學教授傅君勱參與負責重新設計程序。在北京大學的鄧小南教授帶領下,北京大學中國古代史研究中心的研究生負責修訂和審核數據庫中的數據。中研院歷史語言研究所柳立言教授向CBDB項目提供了數字化的資料。有賴多個數據庫項目的參與和共同努力,CBDB在數據的時代跨度和數據類型上有了巨大的擴展。CBDB 當前由哈佛大學費正清中國研究中心、中央研究院歷史語言研究所和北大中國古代史研究中心共同擁有。更多關於歷史、資助者、貢獻者的信息,請訪問CBDB項目網站。 | 郝若貝教授去世後,將數據和相關程序遺贈予哈佛燕京學社。當時此數據包含超過25,000個歷史人物,4,500 條書目信息,以及他在歷史地理信息系統方面積累的成果。哈佛燕京學社隨後對此數據失去了興趣,所以自 2005 年開始,哈佛大學的包弼德教授開始著手公開發佈郝若貝的成果,並進行擴展。來自加利福尼亞大學爾灣分校的中國文學教授傅君勱參與負責重新設計程序。在北京大學的鄧小南教授帶領下,北京大學中國古代史研究中心的研究生負責修訂和審核數據庫中的數據。中研院歷史語言研究所柳立言教授向CBDB項目提供了數字化的資料。有賴多個數據庫項目的參與和共同努力,CBDB在數據的時代跨度和數據類型上有了巨大的擴展。CBDB 當前由哈佛大學費正清中國研究中心、中央研究院歷史語言研究所和北大中國古代史研究中心共同擁有。更多關於歷史、資助者、貢獻者的信息,請訪問CBDB項目網站。 | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Sources== | ==Sources== | ||

2018年5月11日 (五) 08:08的版本

中國歷代人物傳記資料(或稱數據)庫係線上的關係型資料庫,其遠程目標在於系統性 地收入中國歷史上所有重要的傳記資料,並將其內容毫無限制地、免費地公諸學術之 用。截至 2017 年 8 月為止,本資料庫共收錄約 417,000 人的傳記資料,這些人物主要 出自七世紀至十九世紀,本資料庫現正致力於增錄更多唐代和明清的人物傳記資料。 本資料庫除可作為人物傳記的一種參考資料外,亦冀可敷統計分析與空間分析之用。

「中國歷代人物傳記資料庫(CBDB)」是關於7世紀到19世紀中國歷史人物的關係型數據庫。截止至2017年8月,CBDB收錄了超過417,000人的傳記信息(包括姓名、生卒年、籍貫、入仕、官職、親屬關係、社會關係等數據)。[1]

目录

History

CBDB 始於社會史專家郝若貝(1932-1996)的工作。[2]郝若貝首次使用關係型數據庫研究宋代官員的社會和家庭網絡。意識到學界缺乏用於研究中國中古社會史的大型數據集之後,他便踏出了搜集數據的第一步,並通過數據分析,試圖對中國歷史的變遷提出一些有意義的回答。郝若貝透過人名、地名、官僚系統、親屬關係和社會關係等欄目來為數據建立結構。 郝若貝教授去世後,將數據和相關程序遺贈予哈佛燕京學社。當時此數據包含超過25,000個歷史人物,4,500 條書目信息,以及他在歷史地理信息系統方面積累的成果。哈佛燕京學社隨後對此數據失去了興趣,所以自 2005 年開始,哈佛大學的包弼德教授開始著手公開發佈郝若貝的成果,並進行擴展。來自加利福尼亞大學爾灣分校的中國文學教授傅君勱參與負責重新設計程序。在北京大學的鄧小南教授帶領下,北京大學中國古代史研究中心的研究生負責修訂和審核數據庫中的數據。中研院歷史語言研究所柳立言教授向CBDB項目提供了數字化的資料。有賴多個數據庫項目的參與和共同努力,CBDB在數據的時代跨度和數據類型上有了巨大的擴展。CBDB 當前由哈佛大學費正清中國研究中心、中央研究院歷史語言研究所和北大中國古代史研究中心共同擁有。更多關於歷史、資助者、貢獻者的信息,請訪問CBDB項目網站。

Sources

CBDB uses wide range of biographical sources to collect information about individuals. These include biographical indexes, biographical sections of official histories, funerary essays and epitaphs, local gazetteers,the occasional writings found in the literary collections of individuals, and various governmental records.[3]

CBDB is a long-term open-ended project. It has already incorporated the data in the three authoritative biographical indexes 傳記資料索引 for Song 宋, Yuan 元 and Ming 明; birth-death dates for Qing 清 figures; the listing of Song local officials; the civil service examination highest degree holders from 1148 and 1256, from the Ming and Qing dynasties, and the kin named in the Ming dynasty records of degree holders; in 2018 is concluding a project to incorporate biographical data from all major Tang period sources and indexes. CBDB also collaborates with other database projects to incorporate their data and provide share CBDB data; these include: Ming Qing Women’s Writings, Academia Sinica's search engine for biographical materials 人名權威–人物傳記資料查詢, and the Pers-DB Knowledge Base of Tang Persons from Kyoto University.[4]

Current projects include the systematic incorporation of data on local officials from local gazetteers and the quarterly record of official postings from the Qing dynasty (縉紳錄)

Limitations and Strengths

CBDB extracts data from extant sources using computational data mining techniques. By preference it uses sources that can be mined systematically because the sources are structured systematically. This means that it does not undertake in-depth research on individuals, although it is possible for qualified researchers to add data to CBDB based on their own research. The aim is to accurately extract and code the data as given in the sources rather than to check the accuracy of the sources. Thus factual errors in a source and contradictory information from different sources may well be be included in the entries; CBDB does not judge one source above another although it does differentiate between a primary biographical source and biographical mentioned in passing in another source. It follows that CBDB at best represents what has survived over time, which is ever less the further into the past we proceed. Currently CBDB persons are for the most part from the seventh through the early twentieth century (from the Tang through the Qing dynasty). It is a sampling of the past. For example, grave biographies (epitaphs 墓誌銘) are an important source for kinship associations, but only a few tens of thousands have survived. Similarly, only a portion of literary collections have survived, although these have yet to be mined systematically. Because of the nature of the sources, career data will be biased toward officials. [5]

Although CBDB can be used for biographical information on an individual it is not meant to serve as a biographical dictionary. Rather it is a a large and growing assemblage of data about persons, careers, modes of entry into office, kinship, social associations and writings that can be queried to see larger trends as they change over time and vary across space. When large amounts of data are taken into consideration a small percentage of errors, whether from historical sources or mistakes in coding, have little effect. A relational database such as this offers much that biographical dictionaries cannot by giving the user the ability to launch queries and set the parameter of the variables.

Over the long term CBDB will comprehensively mine the available sources and will accurately represent the biographical data in China's historical record.

CBDB Contents

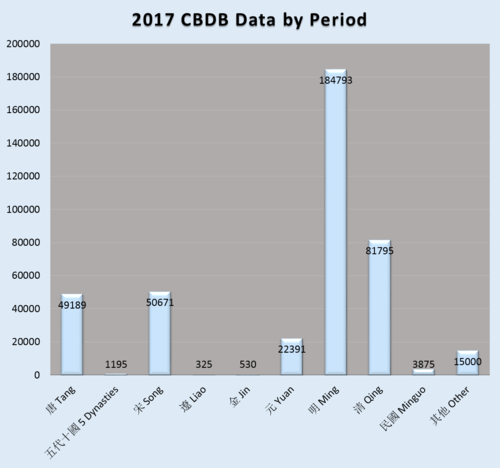

The figure on the right shows persons in CBDB distributed across dynastic periods as of 2018/1. The variation across dynastic periods has much to do with the sources used. For example, the high number of persons for the Ming period is the result of mining the nearly complete record of Ming jinshi degree holders, which includes not only the names of M(other), F(ather), FF, and FFF, but also the names of B+ (older brother) and B-.

By rule CBDB assigns a person to a single dynastic period based on their date of death, although much of their career may have taken place during the previous dynasty. The date of death is lacking for a majority of figures. In these cases we rely on the index year. The index year is a heuristic that represents the surmised time a person was in the sixtieth year of life (60 sui in Chinese terms or 59 years old in Western terms) or the year of death if less than 60. The index year is estimated using a variety of rules, based on averages of all CBDB data. For example, on average men pass the jinshi degree in their thirtieth year, a wife is two and a half years younger than her husband, the first surviving son is born in his father's thirtieth year and so on. Thus if one date is certain within a family then index years can be estimated for other family members. Generally this works well, but if it is extended across more than two generations up or down the reliability of the index year decreases greatly. The index year is essential for queries with temporal parameters.

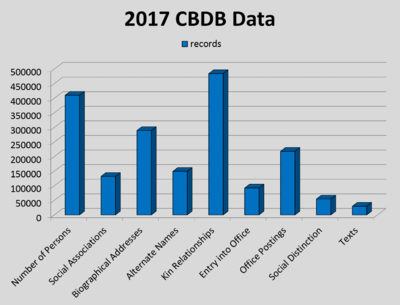

CBDB collects many kinds of data on individuals; the number of data points by category are given in the figure on the left. For each category there is a code table in the database. The main biographical data table assigns each person a unique ID that can be used in various data tables. It codes 235 kinds of Social Associations, which are further categorized by type: the main ones being Writings, Politics and Scholarship. There are 20 Biographical Address codes, including: place of birth, death and burial; basic affiliation (jiguan 籍貫); ancestral address; membership in the Eight Banner system of the Qing dynasty; former address; etc. The seventeen Alternate Name codes include: courtesy name (zi 字), studio names, posthumous name, dharma name, birth order name, childhood names, etc. Every possible kinship relationship in the sources is coded. However, the goal is to reduce these relations to the shortest distance (e.g. F-S(on), H(usband)-W(ife) and rely on computation to generate family trees on demand. Entry into office codes a wide variety of modes of entry, including: many types of examination, recommendation, yin privilege, purchase, etc. Office postings include all office titles and ranks in a dynasty, which in turn can be accessed through a hierarchical tree (allowing one to query all holders of positions within a part of the bureaucratic structure), and places of service for local officials. Social distinction is used in particular to identify the reputation of persons irrespective of office (e.g. poet, artist, monk, merchant). Texts include both the titles of extant and lost works of a person; when possible the bibliographic class is included.

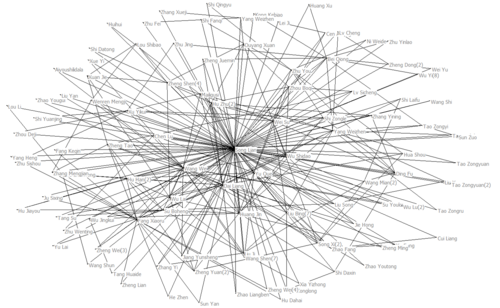

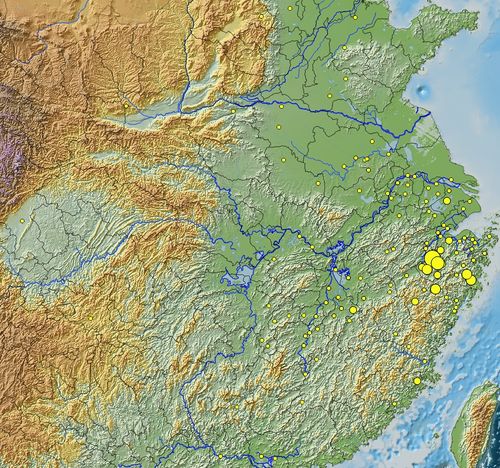

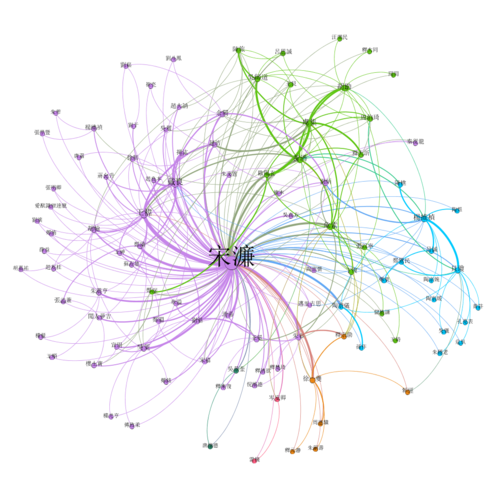

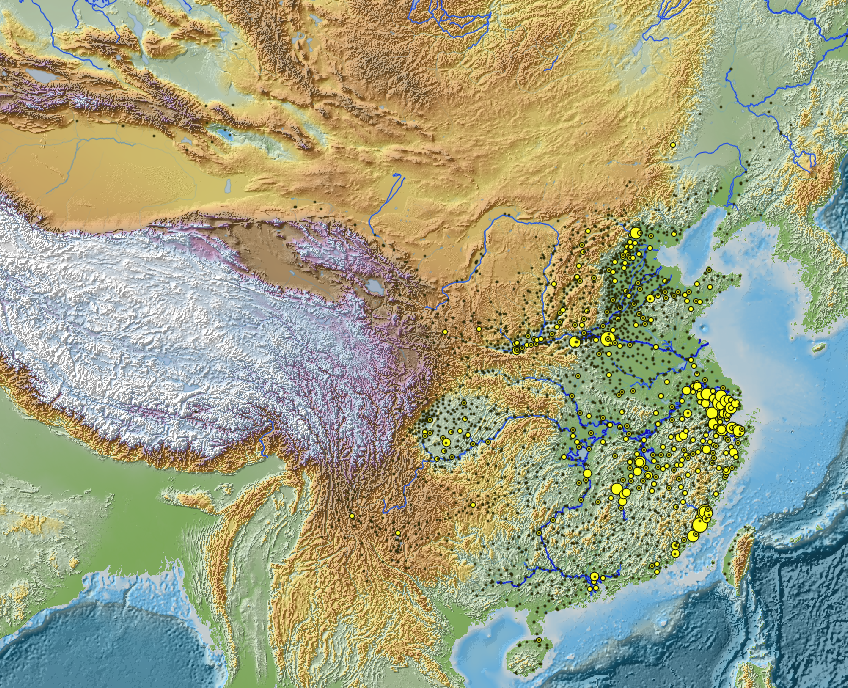

Visualizations

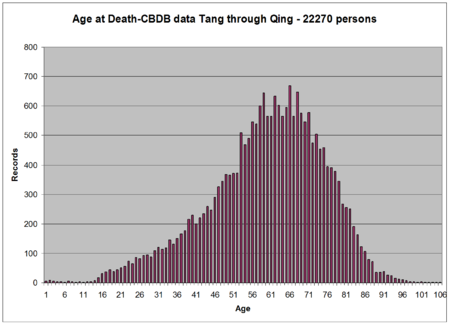

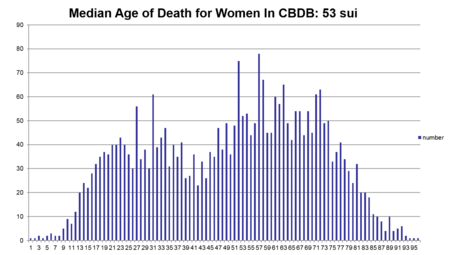

CBDB serves as a data resource for prosopographical research.[6] The data can be queried and then copied into a tool for statistical analysis and visualization. This is illustrated by the two figures contrasting median age of death for all persons in CBDB with the median age of death for CBDB women. The difference, obscured when gender is not differentiated, is due to the higher mortality of women in child-bearing ages. About ten percent of CBDB persons are women.

See also

References

- ↑ China Biographical Database Project (CBDB). Projects.iq.harvard.edu. 2016-11-07 [2016-12-11].

- ↑ Smith, Paul J. "Obituary: Robert M. Hartwell (1932-1996)". Journal of Song Yuan Studies 27. 1997.

- ↑ Fuller, Michael A. The China Biographical Database User's Guide (PDF). China Biographical Database. February 28, 2015.

- ↑ Reviews of Internet resources for Asian Studies. Resource: China Biographical Database Project (CBDB) [New Release] (Jan 2011, Vol. 18, No. 1, 320). The Asian Studies WWW Monitor.

- ↑ New Approaches in Chinese Digital Humanities - CBDB and Digging into Data Workshop. Peking University. Office of International Relations. 2016-01-11.

- ↑ Gerritsen, Anne. Prosopography and its Potential for Middle Period Research (Workshop on the Prosopography of Middle Period China: Using the China Biographical Database). Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 2008, 38: 161–201.

Further reading

- Peter K. Bol, Chao-Lin Liu, and Hongsu Wang, Mining and Discovering Biographical Information in Difangzhi with a Language-Model-based Approach[1]

- Peter K. Bol, "The Late Robert M. Hartwell 'Chinese Historical Studies, Ltd.' Software Project," 1999[2]

- Anne Gerritsen, "Using the CBDB for the study of women and gender? Some of the pitfalls" December 2007[3]

- Fuller, Michael A. "The China Biographical Database User's Guide," February 28, 2015[4]

- "Online Guide to Querying and Reporting System," Academia Sinica[5]ZH:中國歷代人物傳記資料庫

外部链接

- 中國歷代人物傳記資料庫

- ↑ Mining and Discovering Biographical Information in Difangzhi with a Language-Model-based Approach (PDF). Arvix.org. [2016-12-11].

- ↑ Peter Bol. The Late Robert M. Hartwell "Chinese Historical Studies, Ltd." Software Project (PDF). Pnclink.org. [2016-12-11].

- ↑ Anne Gerritsen. Using the CBDB for the study of women and gender? Some of the pitfalls (PDF). Humanities.uci.edu. [2016-12-11].

- ↑ Michael A. Fuller. The China Biographical Database : User's Guide (PDF). Projects.iq.harvard.edu. February 28, 2015 [2016-12-11].

- ↑ CBDB Querying and Reporting System - Online Help. Db1.ihp.sinica.edu.tw. [2016-12-11].