China Biographical Database

The China Biographical Database (CBDB) is a relational database on Chinese historical figures from the 7th to 19th centuries. The database provides biographical information (name, date of birth and death, ancestral place, degrees and offices held, kinship and social associations, etc.) of approximately 417,000 individuals up till August 2017.[1]

Contents

History

CBDB was originally started by the late Chinese historian Robert M. Hartwell (1932-1996).[2] Hartwell first conceived of using a relational database to study the social and family networks of Song Dynasty officials. Aware of the lack of large dataset for research on the social history of middle period China, he took the first step to collect data himself and generate meaningful answers to historical changes through data analysis.[3] Hartwell structured his data around

- people,

- places,

- the bureaucratic system,

- kinship structures and

- contemporary modes of social association.

Professor Hartwell bequeathed the program, which by then consisted of more than 25,000 individuals, a bibliographic database of over 4500 titles, and his work on an historical GIS to the Harvard Yenching Institute. Professor Peter K. Bol at Harvard organized the effort to make Hartwell's publicly available in 2005. Michael A. Fuller, Professor of Chinese Literature at UC Irvine, started to redesign the application, Professor Deng Xiaonan of Peking University led graduate students at the Center for Research on Ancient Chinese History (北京大學中國古代史研究中心) in revising the contents of the database and Professor Lau Nap-yin of the Institute of History and Philology at Academia Sinica (中研院歷史語言研究所) arranged to make digital reference works available for the project. Thanks to the efforts of many the database has been greatly expanded in temporal and coverage scope. CBDB is now owned and administered by the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard, the Institute of History and Philology, and Center for Research on Ancient Chinese History. More information about its history and contributors can be found at the CBDB website.

Sources

CBDB uses wide range of biographical sources to collect information about individuals. These include biographical indexes, biographical sections of official histories, funerary essays and epitaphs, local gazetteers,the occasional writings found in the literary collections of individuals, and various governmental records.[4]

CBDB is a long-term open-ended project. It has already incorporated the data in the three authoritative biographical indexes 傳記資料索引 for Song 宋, Yuan 元 and Ming 明; birth-death dates for Qing 清 figures; the listing of Song local officials; the civil service examination highest degree holders from 1148 and 1256, from the Ming and Qing dynasties, and the kin named in the Ming dynasty records of degree holders; in 2018 is concluding a project to incorporate biographical data from all major Tang period sources and indexes. CBDB also collaborates with other database projects to incorporate their data and provide share CBDB data. These include: Ming Qing Women’s Writings, Academia Sinica's search engine for biographical materials 人名權威–人物傳記資料查詢, and the Pers-DB Knowledge Base of Tang Persons from Kyoto University.[5]

Current projects include the systematic incorporation of data on local officials from local gazetteers and the quarterly record of official postings from the Qing dynasty (縉紳錄)

Limitations

CBDB aims at extracting large amount of data from extant sources through data mining techniques. As a result, social and kinship associations, such as might be known from an individual’s literary collection, and funerary biographies are not exhaustive. Because of the nature of the sources, career data (e.g. ranks and positions a person held), will be biased toward higher offices. Since the database does not require in-depth research into each individuals, factual errors and contradictory information would also be included in the entries, as long as they are from the primary source.[6]

Geo-reference tools

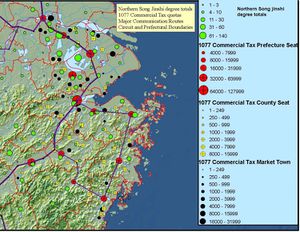

One area in which CBDB could be used is prosopographical research.[7] By combining geographic information system (GIS) software with CBDB, patterns could be mapped out through queries generated from large datasets, for instance, who came from a certain place and what were the social and kinship connections among all those who entered government through the civil service examination from a certain place within a certain span of years, etc.[8] One useful geo-reference tool for the study of Chinese history is the China Historical GIS (CHGIS) project, which makes datasets of the administrative units between 221 BC and 1911 AD and major towns for the 1820–1911 period freely available. Other GIS software such as ArcGIS or MapInfo (or even GoogleEarth) are also compatible with CBDB output.

See also

References

- ↑ "China Biographical Database Project (CBDB)". Projects.iq.harvard.edu. 2016-11-07. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ↑ Smith, Paul J. (1997). ""Obituary: Robert M. Hartwell (1932-1996)"". Journal of Song Yuan Studies 27.

- ↑ Template:Cite book chapter

- ↑ Fuller, Michael A. (February 28, 2015). "The China Biographical Database User's Guide" (PDF). China Biographical Database.

- ↑ Reviews of Internet resources for Asian Studies. "Resource: China Biographical Database Project (CBDB) [New Release]" (Jan 2011, Vol. 18, No. 1, 320). The Asian Studies WWW Monitor.

- ↑ "New Approaches in Chinese Digital Humanities - CBDB and Digging into Data Workshop". Peking University. Office of International Relations. 2016-01-11.

- ↑ Gerritsen, Anne (2008). "Prosopography and its Potential for Middle Period Research (Workshop on the Prosopography of Middle Period China: Using the China Biographical Database)". Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 38: 161–201.

- ↑ "China Biographical Database | Qing Studies". Qing_studies.press.jhu.edu. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

Further reading

- Peter K. Bol, Chao-Lin Liu, and Hongsu Wang, Mining and Discovering Biographical Information in Difangzhi with a Language-Model-based Approach[1]

- Peter K. Bol, "The Late Robert M. Hartwell 'Chinese Historical Studies, Ltd.' Software Project," 1999[2]

- Anne Gerritsen, "Using the CBDB for the study of women and gender? Some of the pitfalls" December 2007[3]

- Fuller, Michael A. "The China Biographical Database User's Guide," February 28, 2015[4]

- "Online Guide to Querying and Reporting System," Academia Sinica[5]

- ↑ "Mining and Discovering Biographical Information in Difangzhi with a Language-Model-based Approach" (PDF). Arvix.org. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ↑ Peter Bol. "The Late Robert M. Hartwell "Chinese Historical Studies, Ltd." Software Project" (PDF). Pnclink.org. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ↑ Anne Gerritsen. "Using the CBDB for the study of women and gender? Some of the pitfalls" (PDF). Humanities.uci.edu. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ↑ Michael A. Fuller (February 28, 2015). "The China Biographical Database : User's Guide" (PDF). Projects.iq.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ↑ "CBDB Querying and Reporting System - Online Help". Db1.ihp.sinica.edu.tw. Retrieved 2016-12-11.