The ever-popular Wordle, like many tools designed to work with digital corpora, can be used on Chinese text with minor tweaking. Wordle takes a text and ranks the words in it in order of frequency, then produces a tag cloud that gives a visual summary with more frequently occurring words in larger letters. Though many tools do this, Wordle’s output is often particularly attractive.

To use Wordle with Chinese, firstly the text has to be split into words using spaces or other punctuation; if not, Wordle will treat each phrase as if it were a word. So instead of “孟子見梁惠王。”, we really want “孟子 見 梁惠王。”. Adding a space between each character is a reasonable approximation for classical Chinese, but obviously means that proper names like “孟子” don’t get treated correctly. Once the text is ready, it can be pasted straight into the Wordle tool (this requires that Java is installed and enabled in your browser). With Chinese text, there are a couple of extra steps. Firstly, on my system at least the default font used doesn’t work for Chinese, so initially instead of Chinese words I get empty boxes. To fix this, go to the Wordle font menu and choose a different font (e.g. “Chrysanthi Unicode”, which seems to work). Secondly, Chinese seems to be detected by Wordle as Arabic, and this results in random words being omitted; click on the “Language” menu in Wordle, and change the setting to “Do not remove common words”.

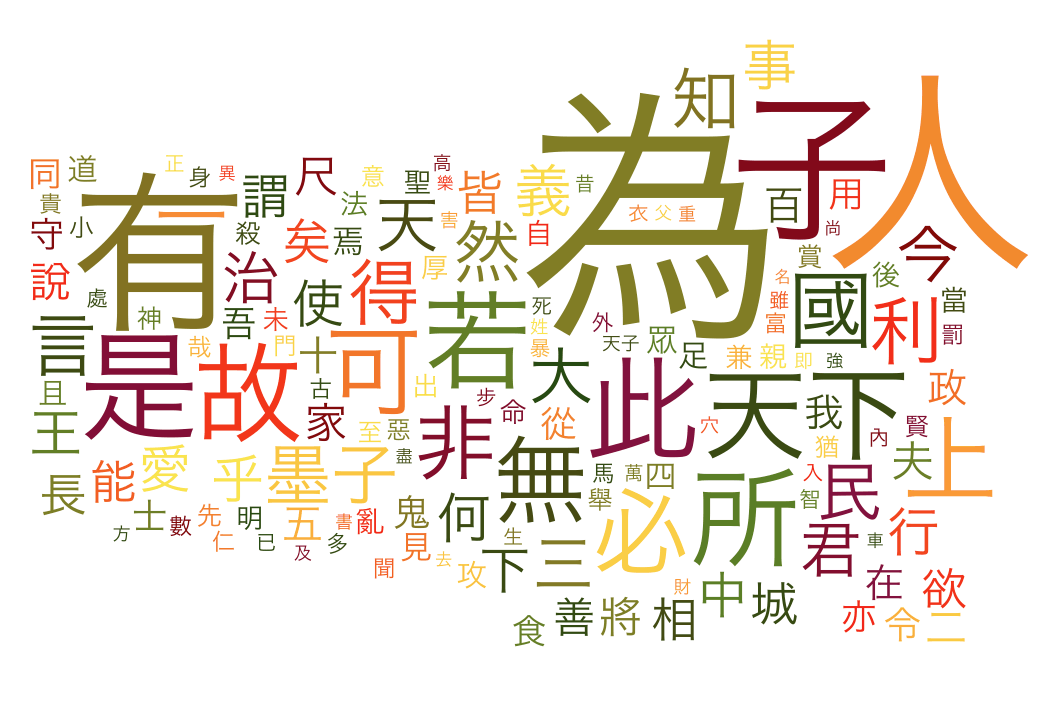

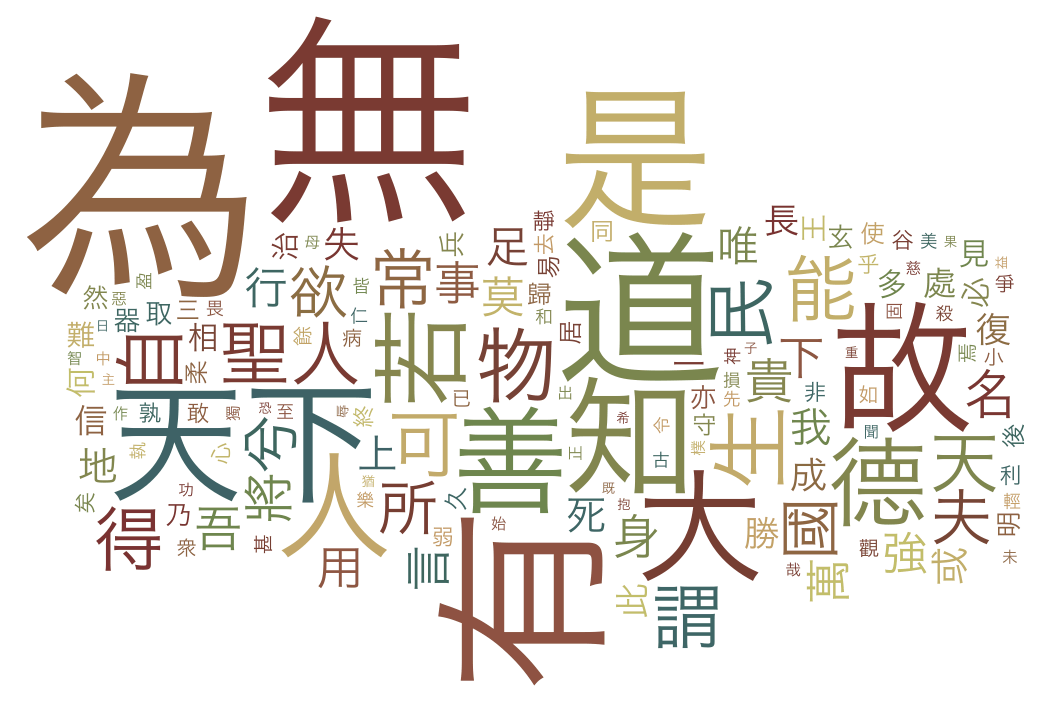

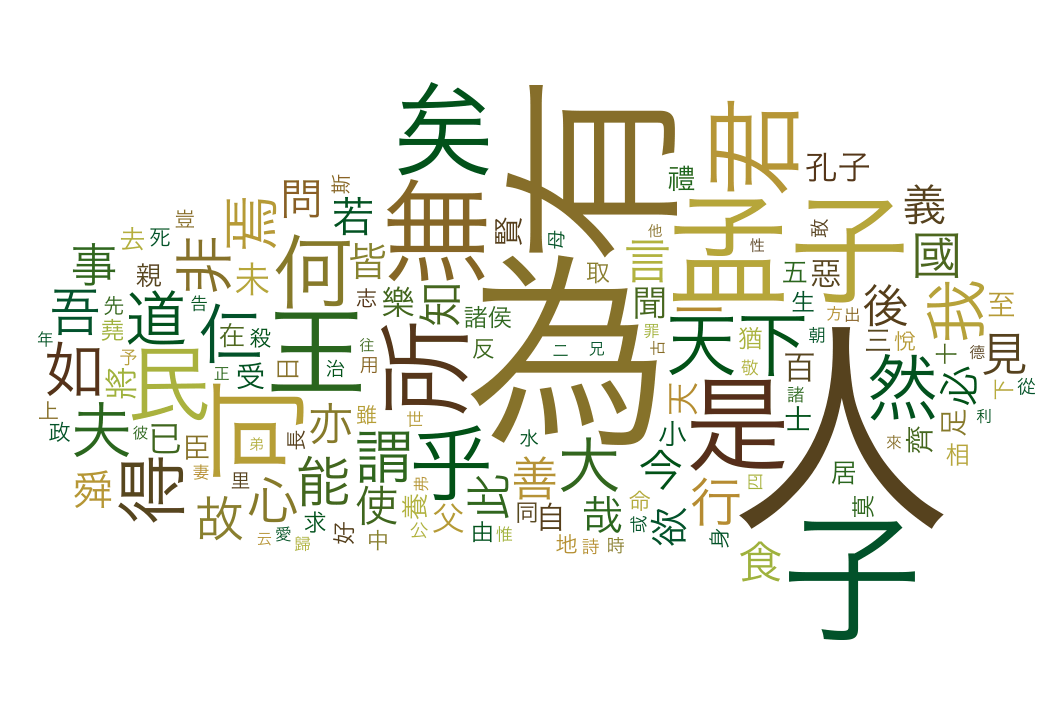

The tag clouds here are of the full texts of the Mozi, Mengzi, Hanfeizi, Xunzi, and Daodejing from the Chinese Text Project – can you work out which is which?

Wordle has the option to automatically remove some of the most common words in a language from the list – so that uninteresting words such as “a”, “the”, “of” and so on don’t appear as giant words overwhelming the tag cloud. Since Wordle doesn’t have a list for classical Chinese, I excluded a fairly arbitrary set of words from the input to produce these images: 也 之 以 則 而 其 曰 者 於 與 于 不. Other particles such as 矣 should probably also be added to this list.

This highlights an important difficulty with word clouds in classical Chinese, however. Words like “無”, “為”, and “有” are very common in classical Chinese texts, but they are also philosophically interesting – in certain contexts and usages. Similarly “故” is a very common and not terribly interesting sentence connective meaning something like “thus” or “therefore”, but is also used to mean “cause”; “是” often simply means “this”, but can also mean “right”, “approve”, or “correct”.

As a result, a highly prominent appearance of 無 and 為 as in some of these Wordles isn’t necessarily an indication that the source was a Daoist text like the Daodejing – in fact if you look closely, you’ll see that in all of these texts 無 and 為 appear fairly often.

Even with these caveats however, this is a much more interesting and aesthetically pleasing way to look at the data than browsing a table of word frequencies.