The Google n-gram viewer allows real-time searching of the frequencies of words and word sequences over time across a large corpus of texts digitized as part of the Google Books project. Without getting into the debate as to whether things like broad cultural trends can legitimately be deduced from these results, it seems clear that access to term and n-gram frequency statistics generated from a large enough corpus at least ought to be able to tell us interesting things about observed word use (though probably with important caveats about things like selection of material).

So the fact that Google’s n-gram results include data for Chinese (albeit only in simplified characters) going back as far as 1500 AD sounds very promising. The online n-gram viewer allows querying of this data, so we can immediately get some results. For example, if we keep the default search scope of 1800-2000 (the authors themselves acknowledge that data gets quite sparse before 1800 so data from earlier than that may be less meaningful), and search for a single character like “万”, we get a nice graph of its frequency over time:

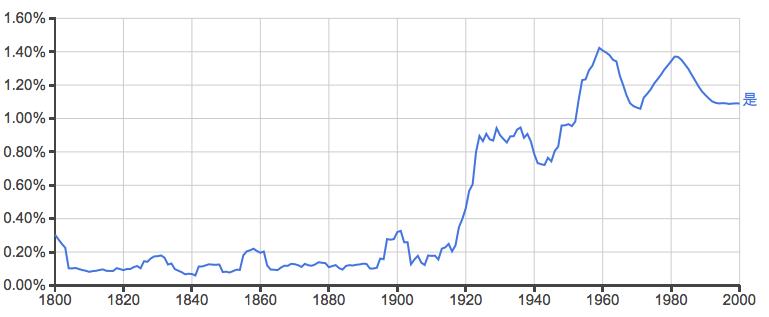

This looks like a good start, although we get noticeably less smooth results from the pre-1960 part of the graph. Trying some other characters, we can get some nice results like this one that seem plausibly attributable to the shift from literary to vernacular Chinese:

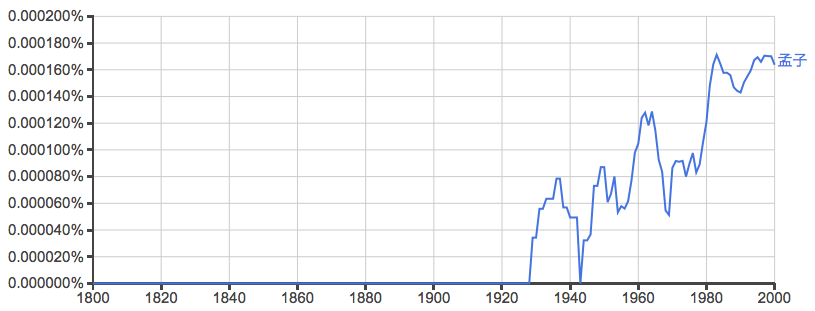

Unfortunately though, further queries quickly show the limitations of the data. According to the Google n-gram data, “Mengzi”, the name both of one of the most revered Chinese philosophers of the classical period as well as the hugely important canonical text attributed to him, is first mentioned in 1927:

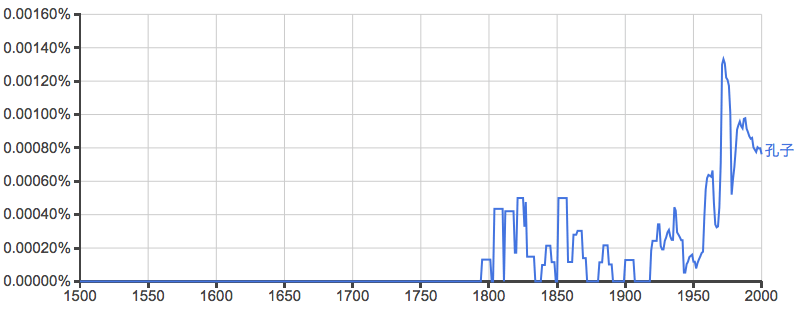

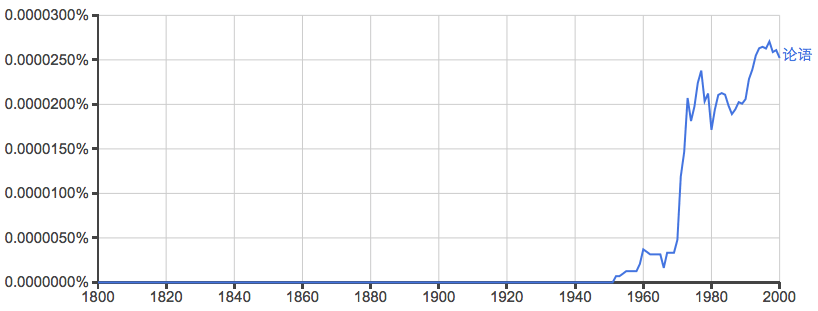

Confucius himself doesn’t fare much better, especially when we go back earlier than 1800 – and the Analects doesn’t even get mentioned once until the 1950s:

Ouch. So it looks like there may be some pretty serious issues with the data even after 1800, and perhaps even as late as 1950. Of course, for a variety of reasons we would expect there to be more data available for the last 50 years or so. How much data is there? Luckily this information is available online.

Looking at the numbers it quickly becomes clear that the pre-modern data is fairly sparse: the first entry is for the year 1510, and has only one volume with 2206 “matches” (i.e. total 1-grams) in the “total counts” file for one single volume of 231 pages. This compares with the first English entry for 1505, with 32059 matches for one volume of 231 pages. Apart from the total quantity of data, one worry is that the number of recorded 1-grams does not seem to fit well with the number of pages – apparently there are fewer than ten recorded 1-grams per page for this volume, which seems improbably few. Adding up the total 1-grams for each year, we get a total of 65195 1-grams by 1560, and by 1900 the figure increases to over 11 million – still less than 0.05% of the total for the whole set (over 26 billion), but definitely enough for us to reasonably expect non-zero results for common terms.

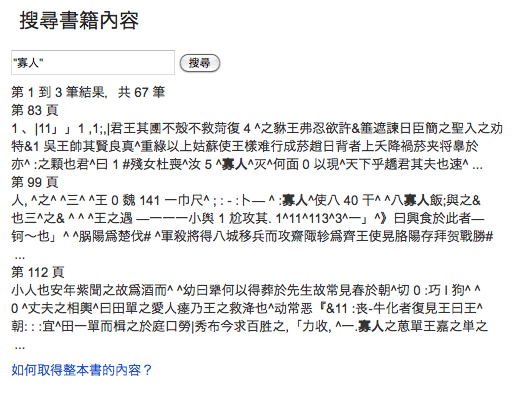

So it does seem surprising that so many results should end up being zero even in cases where Google Books does have some data. For instance, although a search for “寡人” again has no data for any pre-1950 texts, the n-gram viewer itself provides a handy link to “Search in Google Books: 1800 – 1957”, which does return a number of results. This is interesting, because the search results in Google Books also give snippets of Google’s corresponding OCR results. For instance, Google Books has “寡人” occurring on various pages of a book it describes as “馬氏繹史: 160卷年表, 第 13-24 卷”, published according to Google Books in 1897:

Given the apparent errors (although the book is surely in the public domain, no image view or download is available) this book may have been excluded because of poor OCR quality or other reasons, and/or assigned a different date (the text itself being composed earlier than the publication of this edition). (An interesting aside: the results you get for the same search within the same volume of Google Books varies with location. In this case, “寡人” within this volume gets 67 results from Hong Kong, but only 35 from the US.) The first hit looks like it might correspond to parts of this page and the following one on the Chinese Text Project (based on a different edition of the text however).

A final issue that may affect the results is that of tokenization. Since Chinese doesn’t delimit words, the texts first have to be split into words based upon their content. So not every sequence of the characters “寡” and “人” will be counted as an instance of the term “寡人”. This is likely to introduce further problems, partly because it’s a somewhat difficult problem to begin with, but also because it will become a near-impossible task when additional corruption of the source text is introduced through OCR.

In summary, it seems that the Google n-gram data may still need some work before it will be useful for pre-modern Chinese.

Followup post: When n-grams go bad